Deciding whether to continue cropping underperforming areas of fields or remove them from production is a question more growers are asking as the removal of direct subsidies edges closer.

Two difficult seasons that have left some soils in fragile condition may hasten the decision for some, however services leader Matt Ward says the choice between “improve or remove” must consider multiple factors and not be a knee-jerk reaction.

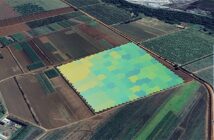

He recommends first assessing crop performance over several years, ideally five or more, to identify areas that consistently yield well, and those that struggle to turn a profit. This can be easily done within Omnia, where an aggregated Field Performance map can be generated from multiple yield maps. The Cost of Production module combines this with costings data (fixed and variable) to show the average cost of production across different performance zones within individual fields, highlighting areas of concern.

“Cost of production can vary anywhere from £70/t to £300/t, so even at a wheat price of £200/t there may still be areas of fields that aren’t profitable.”

If yield maps are not available, Mr Ward notes that Omnia users can also access satellite imagery for the current and previous season to give a more general indicator of potential problem areas.

Pinpoint problems

The next task is deciding what to do with underperforming areas, which requires identifying why crops are not performing. “Poor crop performance may be due to inherent variations in soil type, but issues like shading, pH, poor drainage and compaction are just as frequent,” says Mr Ward.

“For most arable farmers, a good wheat crop drives profitability, so we’ve got to do everything possible to maximise the potential of first wheats.”

Some issues, such as low pH or compaction, can be relatively easily rectified, but others may require significant investment, rotational changes, or removing land from production. This can be a temporary move to help rectify issues, such as putting whole or part fields into a cover crop or temporary grass ley, or a more permanent conversion to other uses, such as targeted establishment of stewardship features, if profitable production cannot be achieved.

Defra’s Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) promises to open new opportunities and income sources for alternative land uses, including habitat creation, flood prevention, and carbon capture. Although details are still being developed, identifying potential sites and opportunities now ensures growers can react quickly once schemes are available, and makes business sense in the meantime, he says.

“Take carbon, for example. Fertiliser and fuel are two major drivers of the carbon footprint, so using them efficiently drives productivity, improves efficiency and saves carbon. That’s a win-win.”

Risk versus reward

Individual growers’ attitude to risk plays a big part in the “what to do next” question.

At a wheat price of £150/t for example, there is a greater risk of not making a profit on less productive areas than there is at a price of say £200/t.

“Taking the high-risk [i.e. less productive] areas out of production gives a greater chance of success, but it is down to an individual’s attitude to risk.

“The important thing is to use all tools available to make informed decisions, considering all options.”

When it comes to managing the best-performing areas, this is the focus of Hutchinsons trials this season, examining how inputs should be used to maximise productivity in zones of higher yield potential.