If agricultural production has not become sustainable by 2030, it will be “incredibly hard” to make up for lost time while also ensuring food security for a rising global population

Agriculture has just over a decade to adapt and evolve to new ways of working that will enable it to feed a growing global population without causing lasting damage to the environment, says Achim Dobermann, director and chief executive of Rothamsted Research.

In a vision statement that concludes the institute’s annual report, released online today, Dobermann looks ahead to 2030, the year when the current 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations end.

“That is all the time we have to make the more transformative changes towards a more sustainable development path. And if we fail, it’s going to be incredibly hard to catch up afterwards,” notes Dobermann. He goes on to highlight what could be achieved by then.

Dobermann foresees the elimination of extreme poverty; revitalised yields of the world’s staple cereal crops with traits that make them more healthy and resistant to damage; and novel plants producing fish oils and pharmaceutical drugs.

“In 2030, and not only in the English west country of our colleagues at North Wyke, we will have healthy cattle and sheep that produce high quality beef and lamb in a natural environment that is managed sustainably with low environmental footprints and no toxic leaks into air or water,” he says.

“In the UK and globally, in collaboration with industry, we must focus on solutions, and I stress solutions, for agriculture,” insists Dobermann. “Just as importantly, our goals must also meet high environmental standards and not only productivity targets. We can do this.”

Elsewhere in the report, the main themes of the institute’s work in 2016-2017 are productivity, engagement and new discoveries. The report also reflects on the achievements of the past five years, from 2012 to 2017, the period of the former strategic plan.

“We helped to found three of the UK’s four new agri-tech centres, staged a popular forum on innovation and, with the NFU, came up with what’s needed for a UK agri-science sector outside the EU,” recalls Dobermann in his foreword.

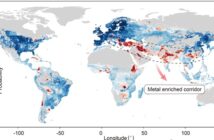

On research, Dobermann notes: “We are pioneering a chemical spray for enhancing crop yields; we showed that damaged biodiversity can recover; and we revealed nutritional risks facing 1 billion people worldwide.”

The report also looks at the institute’s international activities over the past year; its taking over at the helm of the Africa Soil Information Service (AfSIS); the fruits of its continuing alliance with Syngenta; the opportunities for postgraduates at Rothamsted; and its public engagement activities.

The leaders of the four strategic programmes between 2012 and 2017 (20:20 Wheat; Delivering Sustainable Systems; Designing Seeds; and Cropping Carbon) summarise the science and impact of their teams’ work.

The heads of the four National Capabilities of the same period (Rothamsted Insect Survey; Long-Term Experiments; North Wyke Farm Platform and Pathogen-Host Interactions Database) have done similarly.

“There’s no doubt that 2016/17 was a ‘critical period for us’, as I predicted in the last annual report,” says Dobermann. “We came through it all, and with flying colours.”